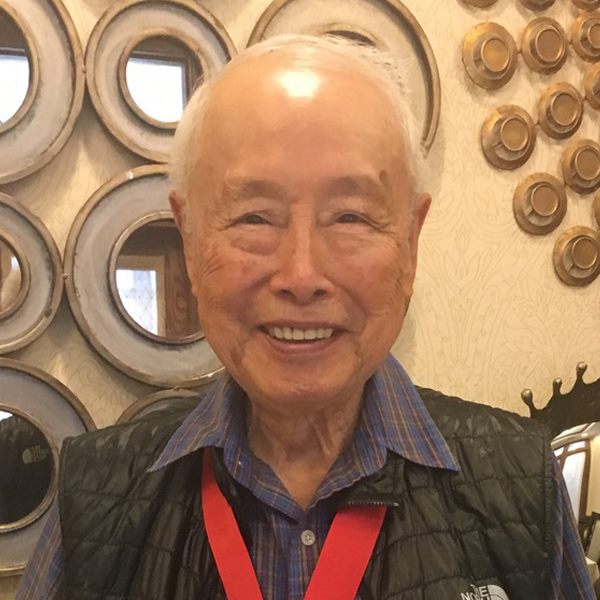

Francis Lee: A Lifetime of Innovation

Hertz Fellow Francis Lee has worn many hats over his long career: engineer, professor, entrepreneur.

The label he relates to most, though, is the one that brings him the most joy. “I consider myself an inventor,” he said. “I like creating new things and having fun.”

Just shy of 95 years old, the oldest living Hertz Fellow was among the second group of scientists awarded the fellowship, in 1964. The Chinese immigrant who became a naturalized citizen was 37 years old at the time and attending the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. There he resumed the PhD studies he had begun in 1952 and paused after two years to focus on his research career in the burgeoning field of computer science.

In the ensuing decade, Lee ticked off several notable achievements that contributed to the United States’ technological prowess: helping create the first digitally controlled milling machine, working with supercomputers, and developing a forerunner of cache memory—more than many people accomplish in a lifetime.

Lee was just getting started.

Journey to America

Lee’s story, which he has chronicled in journals, starts in Nanjing, China, where he was born in 1927 and where his father was an English literature professor. In the midst of World War II, he was a young teenager, laying the foundation—although he didn’t know it then—for what would become a life in America.

“I missed the deadline to enroll in a school, so my parents decided to have me tutored,” Lee wrote. “Father tutored me himself in English. He taught me phonetics using the international phonetic alphabets, which turned out to be quite useful 30 years later in my PhD thesis work. I was 13 years old.”

Lee’s language skills eventually led to him serving as an interpreter for the Allied forces, with the US Office of Strategic Services. Following the war, the Chinese government held an exam for returning interpreters, with the promise of awarding 100 scholarships for overseas study to those who passed.

“I took the exam, and in very short order found my name amongst the lucky 100,” Lee wrote.

Winning a scholarship was one thing. Getting to the United States was quite another, as Lee soon found out.

“Civil war was raging in the northern part of the country,” Lee chronicled. “The students demonstrated against the government, wanting the civil war to stop. I was caught up in the spirit of the time and participated in a number of such street demonstrations. Before long, my mother was tipped off by someone in the police department. My name was on a blacklist and I should go away to wait out the turmoil.”

Lee flew to Wuhan and lived alone, waiting for the tumult to subside and completing applications to several universities in the US. He was soon accepted and decided to enroll at his first choice, MIT.

“I went to the Ministry of Education asking for the release of the scholarship money,” he wrote. “Due to the dire economic situation because of the deepening civil war, I was told there would be no money to fund the scholarships. Those who can muster money on their own could be issued passports. I got my passport, taking one step at a time.

“This was the end of July 1948. I still needed to get my visa,” Lee wrote. “The nearest American Consulate was in Shanghai. However, I learned that it was swarmed with visa applications and it would take several months of waiting time. I decided to fly to Wuhan to get my visa at the American Consulate there, where the waiting line would be much shorter.”

One trip to the consulate got Lee what he needed—including, serendipitously, information about what would become his new home. The consul, a Harvard graduate, shared with him tidbits about Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Lee flew back to Nanjing, and he and his mother took a train to Shanghai, where she bought him warm clothing and booked his passage on the USS General Gordon. A week later, on Sept. 22, 1948, Lee boarded the ship that would journey more than 7,000 miles to America.

“I waved to my mother on the pier. She waved back. Slowly, slowly, as the ship pulled farther and farther away, she merged into the mass of people and disappeared from my sight. I did not know that I was never to see her again."

Making his mark

Immersing himself in his studies at MIT, Lee attained his bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering in just two years, his master’s degree in one, and spent two years in the PhD program before withdrawing in 1954. That year, he became a naturalized US citizen, 10 days before Thanksgiving.

Lee focused on his research career, joining the Servomechanisms Laboratory at MIT, where he was a research engineer working on the first digitally controlled milling machine. This development led to the Automatically Programmed Tool Language, which became the world standard for programming computer-controlled machine tools.

Continuing to follow a path of computing pioneers, Lee joined the BIZMAC Computer Division of RCA for a year before leaving to join the UNIVAC supercomputer division of Remington Rand, which patented Lee’s universal code translator and reversible code converter inventions. In 1963, Lee began a one-year appointment working on Project MAC, a time-sharing multiple access computer being developed at MIT, where he worked on speeding up computer memory, developing a forerunner to cache memory.

At the end of the appointment, he was awarded the Hertz Fellowship and resumed his PhD studies at MIT. Married with four young children, and with just one month of expenses in savings, the Hertz Fellowship provided the means to finish his degree.

Working with the Cognitive Information Processing Group in the Research Laboratory of Electronics, Lee continued inventing, working with his group to develop a reading machine for the blind, the first system that would scan text and produce continuous speech. The research was the basis for Lee’s PhD thesis on the method he developed for converting printed words into phoneme-based spoken language.

Father of inventions

Awarded his PhD in 1965, Lee balanced academia and entrepreneurship for the next 20 years. He joined the MIT faculty the same year he graduated, serving as a professor of electrical engineering and computer science until becoming emeritus in 1987. With engineer Charles Bagnaschi as a junior partner, in 1969 he founded American Data Sciences (later known as Lexicon Inc.), where they focused on applying digital delay to audio technology and language instruction.

A constant thread ran through his work at both MIT and Lexicon: Lee was always inventing.

With MIT colleague Stephen K. Burns, he applied digital design to electrocardiography, creating a digital delay device that allowed heartbeats to be monitored with a continuous moving image.

He parlayed this technology to the live sound industry, working with Lexicon partner Bagnaschi to create the first digital signal processor, introducing the concept of digital delay. They next created Varispeech, an electronic speech compressor for use in the language instruction market.

An advanced version of this technology, the Time Compressor Model 1200, allowed broadcasters to show movies and recorded programs at an accelerated rate without audio distortion, which meant programming and advertisements could fit into time slots without cutting.

The invention was not without controversy, with critics charging that it was analogous to colorization of black-and-white works. For some artists, though, it was an invitation for experimentation. Musician Pat Metheny, for example, used it extensively in his jazz compositions, and filmmaker Stanley Kubrick employed it to intensify battle scenes in “Full Metal Jacket” by speeding up the gunfire.

In 1984, Lee’s invention was awarded an Emmy for its technical contributions to editing.

Lee retired from MIT in 1987 and sold Lexicon in 1995. Today, he resides in Burlingame, California, a small city on the San Francisco Bay. Talking with the Hertz Foundation via Zoom, Lee was modest about all he has achieved.

“I was just having a good time,” he said. “I am just an ordinary person who likes to create things.”